If there’s one defining characteristic of Vince Gilligan’s television series, it’s a sense of place: Albuquerque, New Mexico, in Breaking Bad and Better Call Saul, and the title city of Battle Creek, a Michigan town best known for concocting delicious breakfast cereals. No, make that two defining characteristics. His shows also feature witty banter delivered by—make that three characteristics—fantastic actors exhibiting extremely wide ranges.

With apologies to Monty Python’s “Spanish Inquisition” sketch and Elizabeth Barrett Browning, there’s simply no singular avenue to count the ways Gilligan’s programs reward viewing. The question is, how can he top what is regarded properly as one of television’s all-time best episodic programs?

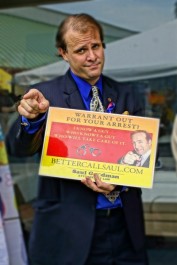

For AMC’s Better Call Saul, the answer was to return to Albuquerque and the theme of ethical shortcuts employed to circumvent personal difficulties. Already, in the show’s first six episodes, we are witnessing several layers of sleaze cocooned over Jimmy McGill, a.k.a. “Slipping Jimmy,” a morally compromised chrysalis that will eventually emerge as Saul Goodman (as in, “It’s all good, man”). When we meet Jimmy in Better Call Saul, he’s a fast-talking sharpie attorney whose moral center derives from the not-always-honorable aspects of popular culture, which he quotes constantly, accurately, and often hilariously.

Jimmy’s success, especially compared to the life of his brother Chuck (the perfectly cast Michael McKean), is measured by his ride, a patched-together Suzuki Esteem, and office digs in the back of a nail salon. From this perch, Jimmy seeks to right the perceived wrongs against Chuck by the partners in the law firm Chuck founded before succumbing to acute reactions to all things electrical and magnetic.

As Jimmy’s character foil, Patrick Fabian’s Howard Hamlin is equal parts egomaniac and smooth-talking voice of reasonable manipulation, and further proof of the show’s bulletproof casting (a list that should also include Rhea Seehorn as Hamlin, Hamlin & McGill attorney Kim Wexler, also extracurricular confidante of Jimmy and Chuck).

Reprising his characterization of Saul from Breaking Bad, Bob Odenkirk adds several shades to the role only fleetingly observed in the original series. Not that Saul wasn’t consistently entertaining and Odenkirk able to hold his own against such incomparable acting talent as Bryan Cranston, Aaron Paul, Giancarlo Esposito, and—more on this below—Jonathon Banks.

If anyone suspected the prequel—Saul takes place five years before Breaking Bad—would resort solely to the title character behaving nonsensically and merely offering glib pop-culture references in the pursuit of the easy laughs comedy veteran Odenkirk could easily elicit (his work on The Ben Stiller Show and Mr. Show being the gold standard of 1990s sketch comedy), the first five minutes of the pilot put them to rest. The sadness and paranoia on the face of the Cinnabon worker in Omaha, Nebraska, is palpable, in a sequence with no dialogue and Odenkirk’s face obscured by a bushy mustache. Filming the sequence in black-and-white was also an inspired choice.

Compelling from the beginning, if only to establish the history of Slipping Jimmy back in his days of hustling payoffs from business owners after falling on their poorly maintained icy sidewalks, the show’s first few episodes brought back Raymond Cruz’s funny yet terrifying future drug kingpin Tuco Salamanca from Breaking Bad.

But if Odenkirk is the show’s star, the Emmy for Best Supporting Actor goes to Jonathan Banks, if only for his performance in Episode Six, which centers on the long-anticipated back story of his character, Mike Ehrmantraut, the resourceful fixer from Breaking Bad who first pops up in Saul as a by-the-book parking booth attendant who quickly reveals himself to be much, much more.

Without giving anything away, the episode is easily the best hour of television this writer has witnessed since Walter White shuffled off the mortal coil to the strains of Badfinger’s “Baby Blue.”

With Gilligan’s mastery of serial television so firmly established—from The X-Files to Breaking Bad and now to Saul—the standalone episodes of CBS’s new series Battle Creek, which he co-created with House’s David Shore, thus far lack the seamless blend of humor and drama of Gilligan’s best work. Instead, the characters thus far seem more like the caricatures depicted in the final seasons of House.

I found the show’s second episode better paced and written than the series’ pilot, but just barely. This is not to target unfairly a show in its infancy. Given the charms of such stars as Dean Winters and Janet McTeer and such guest stars as Duke Davis Roberts (a standout as Choo-Choo on this season’s Justified), Battle Creek warrants further investigation before rendering a final opinion. House’s Kal Penn, riffing on his Kumar character, also costars, along with the quite lovely Aubrey Dollar and Liza Lapira.

An interesting thematic element so far has been the competition between the two main detectives: Winters’ scruffy, old-school cop Russ Agnew and Josh Duhamel’s smooth and well-budgeted FBI Special Agent Milton Chamberlain. Agnew takes illegal shortcuts and charges ahead without much of a plan, whereas Chamberlain uses more expensive and technically advanced but perfectly legal means, yet the FBI agent’s tactics seem no less questionable from a constitutional perspective. That’s an interesting observation, but so far Battle Creek has not been up to Gilligan’s high standard.

Probably doesn’t grab you or me because Gilligan came up with it before the experience of BB. As I understand it, this is mostly a David Shore project with little involvement from Gilligan beyond that filed-away idea. I too was disappointed with the opener. I think it was a Grantland essay that made a key difference clear to me: most shows have “engines,” a canned plot structure they follow week after week. In this way Battle Creek is of a piece with every other procedural on TV, good or bad, while Saul and BB and a few other shows unfold more as a novel, with each episode as a chapter. (Also worth noting–someone should write about it–that for all the welcoming talk of the new long-form series in TV, soap operas were doing the long form decades ago, just without the thoughtful writing and plotting. A chasm of a difference, to be sure, but the form itself is not new.)

Oh, yeah, Mike: You can take it back to radio serials, the old movie serials as well and Charles Dickens serializing his novels in the 19th century. Edits eliminated my distinguishing between the serial aspects of BCS and the stand-alone episodes of BC. Another show on Gilligan’s resume is The X-Files, which blended the “Where’s the Samantha/Who’s the Cigarette Smoking Man and What’s He Up To?” serial storyline with some outstanding stand-alone episodes (“Jose Chungs from Outer Space” immediately comes to mind). As far as prime time television is concerned, Roots/Rich Man, Poor Man/The Thorn Birds originated the “novel for TV,” but the form really took off with the Sopranos, The Wire and beyond. Now some of the best visual entertainment is on basic cable — Justified being but one outstanding example. My wife and I used to go to the movie theater on a regular basis, but when the only thing appealing for a $10 ticket seems to be an animated stuffed bear you know movies are in trouble due to quality television programming.