A classic type of literary and folk-tale character is the trickster, an individual who routinely and comically transgresses the boundaries of acceptable social behavior. From Br’er Rabbit to P. G. Wodehouse’s Stanley Featherstonehaugh Ukridge and Uncle Fred to Bugs Bunny to The Joker of the "Batman" comics to Susan Vance in Bringing Up Baby to the con artists in Hustle, the trickster is a pre-moral or non-moral character whose schemes take ordinary people out of their comfortable existence and force them to react to unfamiliar, morally disorienting situations.

A classic type of literary and folk-tale character is the trickster, an individual who routinely and comically transgresses the boundaries of acceptable social behavior. From Br’er Rabbit to P. G. Wodehouse’s Stanley Featherstonehaugh Ukridge and Uncle Fred to Bugs Bunny to The Joker of the "Batman" comics to Susan Vance in Bringing Up Baby to the con artists in Hustle, the trickster is a pre-moral or non-moral character whose schemes take ordinary people out of their comfortable existence and force them to react to unfamiliar, morally disorienting situations.

In so doing, this type of character both identifies the regnant social boundaries for us and causes us to think about whether the rules make sense.

This is an important process in a liberal society, as social boundaries should be based on common sense and the consequences that personal choices impose on society and individuals. As conditions change—due in great part to technological advances—we must alter our social mores and rules in order to reflect the different world in which we live.

This process is ongoing in any reasonably free and healthy society, and it is an essential element in achieving the balance of liberty and order that makes a good life possible.

The trickster initiates this social process in the life of an individual or small group, and thereby reminds us of the value of the process while entertaining us with an amusing extravaganza that is the modern equivalent of a medieval Feast of Fools—which is common to most societies as a ritual or an art form.

Conservatives and radicals are in greatest need of the trickster’s lessons, as his activities challenge their comfortable, platitudinous certainties. Hence he routinely singles them our for special torment.

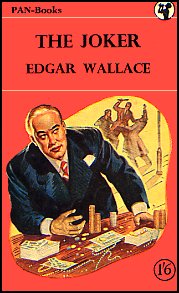

In the following review-essay, correspondent Mary Reed looks at a classic mystery novel that includes a character exemplifying the trickster. The Joker, written by the prolific early twentieth century novelist Edgar Wallace (The Four Just Men, Sanders of the River, the story on which King Kong was based, etc.) was first published in 1926 and is available for free online here.

The Amusingly Wrong Side of the Law

Review of The Joker, by Edgar Wallace

By Mary Reed

As the story opens, Stratford Harlow is on his way to meet solicitor Franklin Ellenbury in Devon, England. Harlow sees a convict working party returning to Dartmoor Prison, and on a whim he decides to go back to the hotel he has just left and summon Ellenbury to come to him.

We know right away who else is on the wrong side of the law, since when Harlow instructs Ellenbury to pretend they are strangers when they meet at the hotel. Ellenbury cannot refuse this or any other summons, for Harlow has helped him pay debts and replace money embezzled from clients. Indeed, Ellenbury is still receiving money from Harlow in payment for his participation in certain of Harlow’s financial dealings.

We know right away who else is on the wrong side of the law, since when Harlow instructs Ellenbury to pretend they are strangers when they meet at the hotel. Ellenbury cannot refuse this or any other summons, for Harlow has helped him pay debts and replace money embezzled from clients. Indeed, Ellenbury is still receiving money from Harlow in payment for his participation in certain of Harlow’s financial dealings.

By changing his plans and returning to the hotel, Harlow notices and eventually scrapes up acquaintanceship with Aileen Rivers. She’s on her way to visit her actor uncle, Arthur Ingle, now doing a stretch in Dartmoor for forgery and fraud.

Harlow, a multimillionaire, is an unusual rogue. He enjoys his "jokes"—many would call them criminal—no end, so it’s not surprising the name of Sub-Inspector James Carlton of Scotland Yard comes up in conversation between Harlow and Ellenbury. Several months later, in typical Wallace fashion, Carlton meets Miss Rivers by accident (literally) on the Thames Embankment. Fortunately, she is only shaken and her elbow slightly injured, but he insists on escorting her home.

Miss Rivers is looking after her uncle’s flat while he’s in durance vile and when it is burgled she calls Carlton for help. While he’s there, Harlow shows up out of the blue to offer her a job or so he says, but suddenly faints and when recovered leaves in a hurry. Carlton has his eye on Harlow, but the latter has covered his tracks so well it looks highly unlikely Carlton will ever be able to pinch his prey.

What follows is a gallop through a plot featuring a couple of laugh-out-loud moments, burglary, a man held a prisoner in luxurious surroundings, underground rooms, a sinister housekeeper, fortunes made and lost, and strange goings-on in the House of Commons, among other shenanigans.

My verdict: Stratford Harlow is one of those engaging villains readers feel they should boo and yet there is something charming about him, as Miss Rivers freely acknowledges. Wallace engages in some wonderful misdirection, and while his characters and situations are in true detective fiction fashion not always what they seem, he manages his literary sleight of hand so well readers will almost certainly be surprised when at the end of the novel they learn . . . well. i won’t say what. Read it and find out!

Thanks, Mike, and thanks for your comments and other contributions. Do you happen to have read any of Erle Stanley Gardner’s Lester Leith stories? From a moral perspective they’re among the best con artist stories ever written. I mention them briefly here, along with some other Gardner series with which you’re undoubtedly familiar.

S. T.:

I have read only Edgar Wallace’s short fiction so far. As has been remarked, he wrote books like his hair was on fire; moreover, he was a writing machine who churned out more tomes than I will be able to read in a lifetime (assuming I don’t set aside all other reading). The short fiction I’ve read is of a consistently high quality, with only a few stories not living up to expectations (not surprising given the volume of his output).

Thanks for the fine essay on The Trickster; it has given me a new perspective on my own meager attempts at producing narratives. I’m saving it to the C drive forthwith.

Also, thanks for printing Mary Reed’s article. She is a reader whose reviews are perceptive and engaging.

Best regards,

Mike Tooney