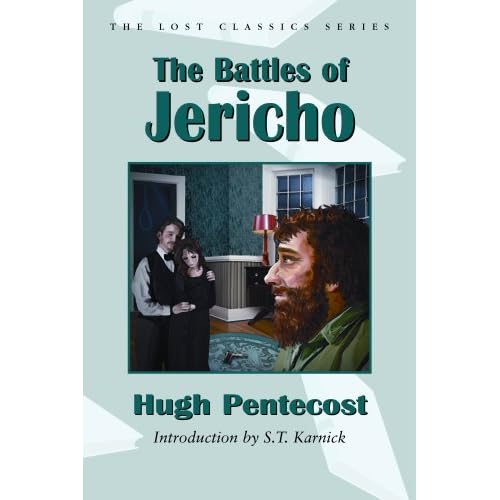

The Battles of Jericho, by Hugh Pentecost, is a superb collection of mystery stories by one of the most prolific and well-liked American mystery writers you’ve never heard of.

The stories, written and published between 1964 and 1976 (all initially appeared in Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine), provide a brilliant snapshot of the turbulent years in which the United States definitively threw off the shackles of traditional manners and morals and adopted a progressive, secular worldview in which individual, immediate gratification became increasingly accepted as the motive for human action.

Given that mystery stories can deal intensively with questions of personal motivation, and that this was Pentecost’s literary modus operandi, it’s a natural thing that the stories in The Battles of Jericho bring the mindsets, attitudes, and behaviors of that period vividly back to life and provide inspiration for serious contemplation and insights.

Published by the indispensable mystery-collection publisher Crippen & Landru, The Battles of Jericho is a beautifully produced book assembled with the publisher’s usual loving care. It includes an introduction written by me, and an afterword by Pentecost’s son, Daniel Philips.

Here are some thoughts on Pentecost and his accomplishments, from my introduction to the book:

If asked to characterize the classic mystery writer—not the best, but the archetypal one—one would do very well to point to the late American author Hugh Pentecost. Ellery Queen aptly described Pentecost as “one of our most professional ‘pros’—a wily tactician and technician who unfailingly excels in playing ‘the grandest game in the world’.”

Pentecost, whose real name was Judson Pentecost Philips, was born in Northfield, Massachusetts, in 1903. He wrote more than a hundred mystery or suspense novels and story collections. . . .

Pentecost served a valuable apprenticeship in the pulps in the 1930s. Strong story lines, colorful characters, lots of action, the ability to create suspense, and an essentially wholesome worldview were necessities for success in the pulps, and Pentecost assimilated those lessons well. . . .

[Like Erle Stanley] Gardner [creator of Perry Mason and author of hundreds of pulp stories], Pentecost was intensely interested in the social implications of his stories, and was even more explicit about it. But where Gardner’s greatest strength was in his brilliantly inventive plotting, Pentecost’s was in his characterizations and settings. . . .

After graduating from the pulps, Pentecost created several successful series detectives, including the sophisticated hotel manager Pierre Chambrun; quiet, unobtrusive psychiatrist-detective Dr. John Smith; New York police detective Lt. Pascal; elderly small-town lawyer Uncle George Crowder; suave, handsome public relations expert Julian Quist; Newsday columnist and investigative reporter Peter Styles; divorced private investigators Carole Trevor and Max Blythe; New York City homicide cop Inspector Luke Bradley; gambler Danny Coyle; and artist John Jericho.

Jericho was the protagonist of more than two dozen stories and six novels published between 1964 and 1987. . . . One can easily see why [Ellery Queen magazine editor Fred] Dannay liked them so much: their combination of interesting settings, skillful puzzles, social concerns, and earnest melodrama matched Dannay’s own approach to his Ellery Queen narratives co-written (mostly) with Manfred Lee.

Jericho is an artist, a painter, but not a prissy aesthete, pseudo-revolutionary, or mocking pop artist, types that were so common at the time. He is a tough Korean War veteran who has seen much violence and horror. He is not an adventurer, however, but a crusader. As in his Park Avenue Hunt Club incarnation, his great concern is for the downtrodden and exploited, and he cannot resist a call for help. And he is a formidable adversary. Not only is he physically powerful and fearless, he is intelligent and perceptive, with an artist’s eye for detail. . . .

Jericho describes his intentions as a painter as follows: “That’s what I hunt for all over the world. . . . The Truth. To be summed up some day in a final statement that will make all of us proud or ashamed, but in either case make us Men. Somehow in color, in design, in the emotional impact of the truth stated in visual terms, I hope to move people more than they can be by words, which can always be twisted around to mean two different things. There are no clever semantic tricks in my paintings.” His paintings, Pentecost writes, display “enormous vitality.” They also show a good deal of anger against social injustice, and as a result they sometimes cause controversy and result in critical dismissal. . . .

Jericho is in his forties and starting to slow down physically, but he was a former commando in the Korean War, and his intellect, insight, and strength of character remain as formidable as ever. Thus the stage is often set for a confrontation between the energy of youth and the wisdom of age. The twentieth century was the Age of Consumerism in the United States, and awareness of that truth was one of Pentecost’s strengths as a writer. He regularly used changing fashions, and individuals’ reactions to them, as a means of characterization. . . .

The stories frequently take place among the wealthy and powerful, but these persons’ privileged status cannot protect them from the encroachments of the immense social upheavals of the times. As social mores broke down rapidly during the 1950s, ’60s, and ’70s, crime transformed from an aberration to be seen on a case-by-case basis, into an immense social problem. Crime fiction reflected this change in attitude, and for many authors that meant increasing interest in the psychological and social factors seen as causing criminal behavior—and sometimes excusing it. Pentecost, however, stayed with the classical approach; in his narratives the emphasis is always on the individual’s choice to commit the crime and their personal responsibility for the consequences.

This makes for an interesting tension in his writings, which is clearly visible in the Jericho tales, as the protagonist’s highly traditional moral sense and thirst for individual justice clash with the chaotic, disturbed activities of the other characters. Philips once said he tried "to write stores that fit into the current climate," and he regularly includes current-events material as background in the Jericho stories. . . .

Pentecost’s concentration on characters’ motives reveals much about the individuals involved and continually encourages us to judge the morality of their choices. That is what good detective stories do, and it is what makes Hugh Pentecost an exemplary mystery writer and one whose stories and novels are still well worth reading.

Like his author-creator, Jericho has a classical liberal point of view: respectful of tradition but welcoming positive change, intensely concerned for the propagation of true justice, a proponent of liberty for all, and a strong and passionate advocate for the weak when oppo

ressed by the strong. He is a true hero and a very interesting and admirable character.

I hope that these excerpts have whetted your appetite to find out more about Pentecost and his writings by reading the rest of the introducation and—much more importantly—to read, enjoy, and appreciate the stories themselves. For more information, click here.

—S. T. Karnick

Haven’t thought of Hugh Pentecost in years, but I remember that I particularly liked the John Jericho stories, when I could find them.