The twenty-five tales of Freddy the Pig, published 1927-1958, constitute one of the classic American children’s book series. Its author, Walter R. Brooks (1886-1958), a prolific journalist and short-story writer who also wrote a couple of adult novels, would be unremembered today without them. As it is, he has to be considered one of the masters of children’s fiction.

Here’s the premise: a farm run by the gruff but kind William Bean and his wife outside the fictional town of Centerboro in nonfictional Oneida County in central New York State is the home to a menagerie of talking animals. (For the first three books they speak in an animal language, but thereafter they speak English, which allows for more interesting interactions with humans.)

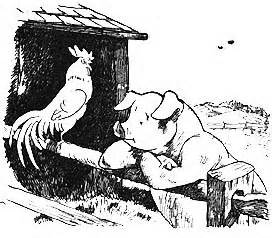

Freddy the Pig becomes the central figure fairly early on, but there is a large cast of characters, both animal and human. Although the plots are certainly serviceable, it is these often vividly drawn characters who are the real strength of the series. One of my favorites is Whibley, a wise, plainspoken, no-nonsense owl. Freddy’s closest friend is perhaps Jinx, the mischievous black cat. There are also Charles the rooster, forever making pompous speeches, and Henrietta, his henpecking but loving wife.

There are mice, rabbits, spiders, horses, dogs, cows, ducks, and others. Aside from some bad animals such as Simon the rat, the creatures are always out for fun when they are not dutifully performing their farm tasks.

Freddy, inspired by his reading of Sherlock Holmes stories, becomes a detective in Freddy the Detective (1932). He also becomes editor of a newspaper (the Bean Home News), president of the First Animal Bank, and head of Barnyard Tours, Inc. He is one of those behind the cow Mrs. Wiggins’ campaign for president of the First Animal Republic in Freddy the Politician (1939). He also writes doggerel, and much of it is gathered in The Collected Poems of Freddy the Pig (1953).

Freddy is a winning character but by no means a super pig. He can make mistakes and become frightened. The tales themselves partake of a variety of genres such as mystery, science fiction, travel, and sports.

Brooks rarely if ever moralizes; his aim is to entertain. Occasionally there is some humorous homely wisdom, as when Whibley says, “It’s always a waste of time explaining to people that you’re not as big a fool as they think you are.” Brooks, as narrator, teaches the reader about animals (e.g., “wasps have a queer sense of humor”).

The tales are good-humored and uncondescending, and Brooks sometimes uses words the typical child is unlikely to know (e.g., ribald). This means the reader will have to get the meaning from the context or look it up; no bad thing either way.

Brooks obviously loved words and the world he created. Luckily, Overlook Press and Puffin Books have all of them in print.

You are welcome. Other good books that come to mind are Charlotte’s Web, Stuart Little, and A Wrinkle in Time.

Shmuel, thank you for bringing this series to my attention. I’ve been compinilg a list of books to share with my young daughter when she begins reading, and am especially looking for titles from earlier, more literate eras. It sounds like these will foot the bill nicely. I’d be interested to hear of any other recommendations you might have.