TAC editor S.T. Karnick is right that Julie & Julia is likely to enjoy a profitable run for the rest of the summer. And while I’m not normally a fan of Nora Ephron movies (I am a man, after all), this film is worth seeing with the love of your life if only to watch Meryl Streep’s charming and captivating Julia Child impression, Jim Lakely writes.

But even in this cute little movie, Ephron can’t help but take political shots at nonliberals—one of which was perhaps the most jarring I can ever remember watching.

My wife and I saw Julie & Julia last night. It was a nice film, but one that is hard to characterize. It’s not quite a romantic comedy—though there are funny moments and the depiction of the genuine, lifelong romance between Julia Child and her husband is the sweetest expression of loving, marital devotion on film since the opening scenes of Up.

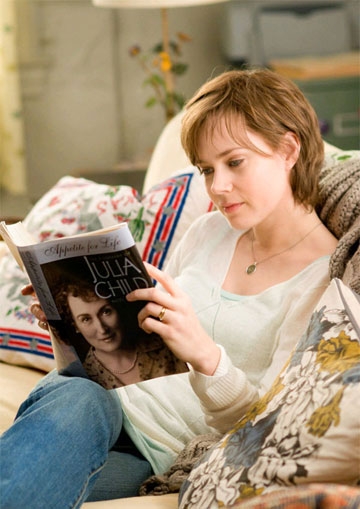

It’s not quite a biopic, either, though it recounts the life Julia Child led starting from he move to Paris after World War II to her finally getting her iconic cooking book published, as well as the much-less-interesting life of the Julie Powell (played delightfully by Amy Adams, who has now taken for good the "Meg Ryan" mantle Hollywood’s been trying in vain to pass off for more than a decade).

In fact, in the dueling plots of the film, one is most struck by how substantive, intelligent, generous, determined and talented Julia Child is compared to the shallow, jealous, defeatist, pseudo-intellectual Julie Powell.

It’s not entirely Julie’s fault. She is the product of a much more narcissistic age, and she gets points for embarking on an ambitious project—trying to cook every recipe in Child’s Mastering the Art of French Cooking in one year and blogging about it every day. And Julie does it because she has genuine admiration for Julia Child.

But as you watch the film, you really wish there were lots more Julia and a lot less Julie. Meryl Streep is probably a good bet for another Oscar nomination. Critics may complain that Streep is merely doing an impression of Child, but that’s to sell the performance short. Yes, Streep has Child’s unique voice spot on, and has captured Child’s mannerisms, as well. But Streep transcends merely aping Child and plays her with nuance, emotion and sophistication. Streep as Julia Child is one of the more entertaining and interesting performances I’ve seen this year.

But now we get to the point of this post—the jarring and totally unnecessary injection of leftist politics that nearly ruined the movie for me and likely countless others who are not partisan liberal Democrats.

WARNING: A FEW SPOILERS AHEAD

There is a subplot in the Julia Child half of the film in which her diplomat husband is worried that they’ll be transferred out of their beloved Paris because of McCarthyism. Paul and Julia, you see, once traveled to China (Julia was posted there working as a file clerk for the OSS). And the evil McCarthy is stirring up trouble back in Washington—trying to destroy the lives of good people who have given their lives to "government service."

Ephron, a committed liberal, returns to this theme several times—all the while leaving out the important fact that despite the excesses of McCarthy, there actually were communists and Soviet agents who had infiltrated high levels of the U.S. government.

Paul is called back to Washington and subject to three days of questioning. He’s exonerated of any communist sympathies, but Paul and Julia are eventually transferred out of Paris. Ephron leaves the audience with the impression he’s transferred because he came under suspicion by McCarthy, even if that is not necessarily the case.

Now, I have not read Julia Child’s memoir, My Life in France, but she does write about the McCarthy hearings and how it affected their life, and it is reasonable to bring it up in the movie. However, by the fifth time Ephron brings it up, it starts to have less of a feel of historical accuracy and more of gratuitous reflection of one of Hollywood’s most popular pastimes: exhuming McCarthy to burn him in effigy. OK. We get it.

And was it really necessary to have to have a scene in which Child argues with her Republican father in Pasadena and Dear Old (and mean) Dad defends McCarthy with a scowl and very nearly some spittle? C’mon. It comes off as ludicrously forced.

But that’s not even the worst of it. Julie Powell works in a cubicle answering phone calls from the development corporation that owned the World Trade Center—in 2002. She gets numerous calls from family members of people killed in the 911 attacks, as well as people complaining about the plans to build something on the hallowed ground. She calls in sick to work one day, obviously feigning illness, and her boss calls her into his office the next day to chew her out. At the end, the boss says, "A lot of people want your job. If I was a Republican, I’d fire you!" Seriously.

That comes from so far out of left field (pun intended) that it rises to the level of unintentional liberal Hollywood self-parody. In fact, it is among the most glaring examples of liberal Hollywood fantasyland thinking I’ve ever seen in a film. It’s so out of place, Powell’s boss might as well have said, "If I was an alien from planet Loon, I’d lick your elbow!"

Let’s remember the context here. Republican New York Mayor Rudy Giuliani was still revered as probably the greatest hero in the history of that great city. Republican president George W. Bush was still riding high in the public opinion polls (even if this screed was delivered in 2003). Republicans were still in control of Congress, and also enjoying similar popularity in the United States. Yet Ephron ignores all this and instead fantasizes that in 2002-2003, ordinary folks were using the word "Republican" as a stand-in for "heartless monster."

The line landed with a thud — like a Cornish game hen slipping off the counter and onto the kitchen floor. Only blind and enduring disgust, if not hatred, for those who differ from one’s political views can explain such a jarring, tin-eared line of dialogue.

My wife is still in the process of reading Powell’s book, upon which the film is partly based, and she informs me that the author peppers the book with gratuitous shots at Republicans (not just politicians, but ordinary people who don’t vote "D" every time) that are similarly out of place. Hence one might surmise that Ephron was trying to reflect the tone of the source material with all this political badgering.

But that’s no excuse for bad writing, The movie would have been more enjoyable, and less insulting to half of its audience, if Ephron left it out.

–Jim Lakely

I wonder if Ephron knows the close relationship that the Kennedy family had with Joe McCarthy. The movie was quite good but the subtle propaganda would serve Goebel’s playbook. Strange that the “Left” imitates the extreme “Right” in its tactics…

Thanks for letting me know. Figures, typical liberal looking for cred. How utterly tedious.

Thanks for the warning, Jim. Gratuitous Republican bashing in a Nora Ephron film doesn’t surprise me in the least. Nor does it surprise me that source material dripping with gratuitous Republican bashing is what Ephron decides to bring to the screen. A few years back, at an Aspen Institute conference, Ephron was asked if she knew any evangelical Christians and/or Bush supporters, and if she did not then how does she know what she knows about “those kind of folks.” Her response was, simply, “No, and I’m not ashamed to admit it.” And she ignored the second part of the question.

After some digging I found a link to that 2006 Aspen Institute panel “Television, Cinema and American Values”, thanks to C-Span. The questions and responses begin at the 36:17 mark. Note the crowds responses to the questions.

That panel and Nora Ephron’s blatant intolerance and bigotry gave me a good idea what I’m going to get from any project with which she’s involved, and it does not dispose me positively toward them.

Thanks for the review, as a Republican, I wouldn’t watch this movie if they paid me.

We almost thought of seeing this but after reading more than one review and seeing the political bashing – FORGET IT! No money for this film! If you can’t make a film without politics then forget it. It has been at least 6 years since we stepped in a actual movie theater.

Pity, I admire Meryl Streep and I really want to see this movie…which now I won’t. I’m just tired of the cheap shots at Republicans. But the same way that Ms. Ephron has the right to demonize Republicans as she like, as a Republican I have the right not to endorse or watch it.

the republican comment is rather funny; because every time i catch one of my employees goofing off, i say, “what are you? a democrat? get back to work.”

Great review, but what are the excesses you allude to? “despite the excesses of McCarthy”

Having read both books, I can say, sadly, the comments on McCarthyism and Julia’s father are straight out of the source material. Paul and Julia Child were definite liberals; the McWilliams of Pasadena were staunch Republicans and never did either side give an inch.

Mrs. Child mentions quite a few times in My Life in France that McCarthyism loomed over their heads like the sword of Damocles while they were in France, but it wasn’t the reason they were transferred to Marseilles or, later, Norway.

Julie Powell’s language and the barbs thrown at Republicans almost ruin what is otherwise a charming book. Despite those, it made me want to find Mastering the Art. . . and become a hermit in the kitchen.

The few barbs thrown at conservatives in the movie are nothing compared to what was available in the source materials. I discounted those scenes and enjoyed the movie quite a lot.

Saw the movie, loved it but must say those republican punches were shots in the dark and did taint the total enjoyment of the film. I chalked it up to hollywoods-need-to-be-political-even-when-there’s-no-need syndrome.

You’re so right, QA_NJ. The Republican bashing was jarring — and wholly unnecessary to the plot. Felt shoehorned into the movie.

And yes. Julie, despite the charms of Amy Adams, does come off as a twit.

But why are you glad you saw it after reading my review. Would you not have seen it because of my review?

Saw the movie yesterday, enjoyed it, recommend it, but was jarred by the ridiculous Republican remarks that were so not part of the overall mood. Read your review just now & glad I saw the movie first. I liked Julie & what she did in it, too bad she comes off as a witless twit in person. I know she couldn’t care less, ‘tant pis.’

While you take, A lot of people want your job. If I was a Republican, I’d fire you!” as a put-down of Republicans, it’s actually a fairly accurate description of the sort of thing oblivious liberals in New York City actually say in the office, assuming that everyone is a liberal like they are. While you may think “New York Mayor Rudy Giuliani was still revered as probably the greatest hero in the history of that great city,” I’ve had liberal co-workers describe him as if he were a Nazi ready to institute a police state in their beloved city. Basically, liberals really do talk that way in New York City.

when i sat through 4 minutes of a tedious and torturous charlie rose interview with streep and ephron, i knew this movie was a ‘must not”.

the hair tossing and ponderous ruminations were mind numbing.

Actually, in the book, Julie’s boss is a Republican (not a Dem as in the movie) and she and he have a kind of playful/argumentative (a la “Moonlighting”) rapport – although there are rips at Repub’s, they are also not completely depicted as monsters.

Just to reiterate: Aside from the jarring and insulting injection of politics, I still (on the whole) liked the movie. It’s a typical Ephron piece of fluff, but one that works because the talent and appeal of the lead actors rises above the script.

I shared with the editor of this fine blog my qualms about revealing so much of the plot — a necessary evil to make my points. The reply: It’s not Hitchcock.

Indeed. It’s Ephron! The title might as well have been “You’ve Got Blog.”

Yeah. I know. My wife actually looked up that very blog post a few days ago and read it to me. She tells me from reading the book that Powell’s shots at Republicans are almost Tourrette’s-like — non sequiturs that have nothing to do with her quest to finish all those Child recipes in one year.

One would think, though, that in the process of editing down a book for movie treatment (especially when you’re using two books for source material), you’d leave the non-germaine stuff out. The reason why that line from Julie’s boss is so jarring is because it has zero context either before that scene or afterwards. The character of Julie, as played by Amy Adams, gives no indication of any animus toward Republicans.

It just doesn’t make any sense, other than as a cheap shot that Ephron couldn’t help but take (with, perhaps, the tiniest of fig leafs by saying it reflects the real Julie Powell’s hatred of Republicans.) It would have been better just to leave all that alone.

Nice review, Jim. I didn’t have much interest in seeing “Julie & Julia” and I have less interest in seeing in now. But I happened to read a review that made a somewhat similar point as yours, which led me to Julie Powell’s blog and this post:

Seems Ephron isn’t solely to blame. She had rich source material from which to draw.