There’s no end to the debate over the greatest rock album, but the question of the most influential rock album deserves more attention. Judging impact is generally harder than evaluating quality, because it extends beyond the merits of a particular record to considering the effects it had on the music that followed.

Even so, some contenders for the “most influential” crown are obvious. For example, Brian Eno famously said the Velvet Underground’s first album didn’t sell a lot of copies, but everyone who bought one started their own band. Many musicians inspired by the Velvets became highly influential themselves, including David Bowie (whose dramatic change in direction post-Velvets arguably made him the most innovative and important rock music artist of the ’70s) and Jonathan Richman (a Velvets fanatic, whose own debut with The Modern Lovers riveted the incipient punk scene when it was finally released in 1976).

Some albums are also credited with kickstarting entire musical genres. Examples include In the Court of the Crimson King, widely considered to be the first progressive rock album; Led Zeppelin II, which set the tone for heavy metal and launched a million air guitar solos; Uncle Tupelo’s debut, which sold even fewer copies than the Velvet Underground’s but spawned the unlikely alt-country and cowpunk hybrids; and Nirvana’s Nevermind, which defined early ’90s “grunge” and much of the alternative rock of the rest of the decade. All were highly consequential, as were critically acclaimed and musically revered classics such as the Beatles’ Rubber Soul and Beach Boys’ Pet Sounds (more on each to follow).

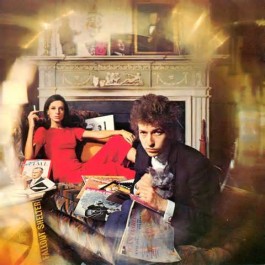

However, one album surpasses all of these and others in influence. More than any other record, it broke the mold and changed perceptions of what rock music could become. That album is Bob Dylan’s Bringing It All Back Home, which was released almost exactly 50 years ago March 22, 1965). Given its 50-year anniversary, now is an appropriate time to take stock of this record’s singular brilliance and seismic impact.

This requires a little context, which will be familiar to longtime Dylan fans but is still worth reviewing. (It was fifty years ago, after all.) Dylan made four albums in the three years preceding the release of BIABH. All were widely seen as “folk” records, even though nearly all the songs on everything but Dylan’s debut were original compositions, not folk standards. Nevertheless, by early 1965 Dylan had become an established presence–a superstar even—in the folk world, which was at the peak of its popularity in the early 1960s.

Dylan, however, had outgrown folk and was increasingly annoyed by its aesthetic strictures and demands for lyrical and social “relevance.” Although he had a deep affection for the richness and mystery of traditional music, Dylan was a rocker, too. In fact, rock and roll was his first love: he played rock music in high school before migrating to New York and falling in with the Village folk scene.

The folkies hated rock and considered Dylan part of their tribe, but by 1964 it was obvious he was changing. This was evident in the title of his fourth album, Another Side of Bob Dylan, which didn’t contain any obvious ‘protest’ songs like those that dominated his two preceding albums. Another Side also included “My Back Pages,” a clear goodbye-to-all-that anthem and declaration of artistic independence. Its famous refrain (“I was so much older then; I’m younger than that now”) was both a repudiation of Dylan’s identity as a protest singer and the announcement of a musical rebirth.

But although Another Side was a lyrical departure from Dylan’s previous work, it still sounded like a folk album. It was almost entirely acoustic. Nearly all the music was played by Dylan himself on guitar and harmonica. Sonically, the folkies still had reason to consider Dylan one of their own, even if he was expressing reservations about being his generation’s voice of protest (reservations that would grow much stronger as the ’60s wore on).

That all changed with the first note of Bringing It All Back Home, the squalling guitar riff that kicks off “Subterranean Homesick Blues.” A torrent of acerbic but playful lyrics rides the song’s honky-tonk rhythms, and Dylan’s singing is simultaneously assertive, world-weary, and bemused. The words flow rapidly, not unlike the “raps” that would later dominate R&B. This was definitely rock, not folk, but a hyper-literate yet down-home kind of rock unlike anything else on the radio in 1965. And “Subterranean Homesick Blues” did get radio play; it was the first of Dylan’s songs (sung by himself, not other artists) to make the Top 40, which is itself a sign of Dylan’s more rock-oriented style.

The second song quiets things down. “She Belongs to Me” is a gentle ode to a lover who is an artist in her own right. It was almost certainly directed to Joan Baez, who was involved with Dylan at the time. The evocative first lines—“She’s got everything she needs/She’s an artist/She don’t look back”—would later be adapted for the title of a documentary about Dylan (Don’t Look Back) filmed later that year. “She Belongs to Me” is a love song and paean to bohemian creativity, but its perspective (e.g. “you will start out standing, proud to steal her everything she sees/but you’ll wind up peeking through her keyhole down upon your knees”) is both bittersweet and ambiguous.

“Maggie’s Farm” is next, and it picks up musically where “Subterranean Homesick Blues” left off. Lyrically, it’s “My Back Pages, Part II,” except Dylan is now taking on the protest music folkies directly and playing it for laughs. “My Back Pages” was high-minded and philosophical; “Maggie’s Farm” is drenched in mockery, with the “family” on the (folk music) farm depicted as knaves, liars, and worse. The lyrics ending the song (before one final, emphatic “I ain’t gonna work on Maggie’s farm no more”) are “they say sing while you slave, and I just get bored,” which pretty much says it all.

“Love Minus Zero/No Limit” follows, and it is one of Dylan’s best songs. It opens with arresting lyrics (“My love, she speaks like silence/Without ideals or violence/She doesn’t have to say she’s faithful/Yet she’s true like ice, like fire”) that only get deeper and more mysterious as the song goes on. The music, by contrast, is light and loose, and Dylan’s vocals glide effortlessly across the lilting melody. It is a delicate, carefully crafted and simply beautiful composition, the closest thing in rock music to a Shakespearean sonnet.

“Outlaw Blues” is the opposite end of the musical spectrum, a raw but restrained rocker that channels Chicago blues rather than Elizabethan poetry. The song fantasizes about living an open-ended, “outlaw” lifestyle that might lead to Australian mountain ranges and muddy lagoons. It’s easy to see how the babyfaced Dylan (only 23 years old at the time) identified with the line about looking like Robert Ford but feeling like Jesse James, especially since he was making a break from his folk music past and lighting out for a new territory.

The next two songs end side one on a hilarious note. “On the Road Again” chronicles the misery of an impossible domestic situation, where, among other things, the singer wakes up in the morning to find frogs in his socks and later gets his face clawed by a pet monkey. There seem to be clear parallels to the torments at Maggie’s Farm, especially when Dylan ends the song by asking his housemate, “Honey, how come you don’t move?”

“Bob Dylan’s 115th Dream” is a surreal reimagining of the discovery of America, with Dylan along for the ride with “Captain Arab.” It is packed from stem to stern with descriptions of bizarre sights, unpleasant encounters, and general mayhem. It’s not exactly a positive portrayal of America, but much of the insanity appears to reflect Dylan’s own hyperactive life at the time. The song opens with Dylan breaking up in laughter on an earlier acoustic take in the studio, which suggests it shouldn’t be taken too seriously, and the clever wordplay, sly jokes, and rollicking beat are all good fun.

Side Two of BIABH is a quite different from side one. It’s fair to say there had never been anything like it in rock music up to that time. It still stands (along with the second side of Abbey Road, and just a few others) as one of the best, and most coherent, sides of an LP record in rock history.

It begins with “Tambourine Man,” and what more needs to be said about this song? Scores of musicians have said “Tambourine Man” utterly changed their views on songwriting. It was a hit for Dylan, and even bigger hit for The Byrds. Its lyrical sophistication and complex rhyme scheme were unprecedented for a Top 40 rock hit.

“Gates of Eden” is even more lyrically complex, and far more ambitious. Its subject is nothing less than the loss of mankind’s innocence, and the travails of human experience since the separation from a metaphorical Eden. Or at least, that is my interpretation. The lyrics are remarkably rich, dense, and laden with potential meaning. No popular singer in any genre had written anything like this before.

“It’s Alright Ma (I’m Only Bleeding)” may be even more ambitious. Unlike the yearning of “Gates of Eden,” “It’s Alright Ma” is filled with venom, with Dylan practically spitting out a steady stream of invective against human vanity, greed, pettiness, superficiality, and hypocrisy. He sings with coiled intensity and total commitment, the words seemingly propelled by his own insistent guitar playing. It is a remarkable, stunning song, with one of Dylan’s best vocal performances, where the artist looks into the abyss and almost succumbs to nihilism, but not quite.

The album closes with “It’s All Over Now Baby Blue,” and its gentle tone is a relief after the full-frontal attack of “It’s Alright Ma.” Although some see this as a song of separation after a relationship has ended, it’s more plausible that Dylan is saying goodbye to his earlier self as he begins a new journey. How else to interpret these words:

Leave your stepping stones behind; there’s something that calls for you

Forget the dead you left; they will not follow you

The vagabond who’s rapping at your door

Is standing in the clothes that you once wore

Strike another match, go start anew

And it’s all over now, baby blue

Here, the stepping stones represent the folk music/protest path Dylan once trod, but the time has come to start anew and not worry about those who used to travel with you. “Baby Blue” is the earlier Bob Dylan the world has come to know, but that identity is all over now.

Overall, Bringing It All Back Home is an outstanding album. The styles and moods it explores are quite diverse, and at least five songs are works of genius: “Love Minus Zero” and all of side two. Two other songs have also become fan favorites and are central to Dylan’s oeuvre: “Subterranean Homesick Blues” and “Maggie’s Farm.”

Overall, Bringing It All Back Home is an outstanding album. The styles and moods it explores are quite diverse, and at least five songs are works of genius: “Love Minus Zero” and all of side two. Two other songs have also become fan favorites and are central to Dylan’s oeuvre: “Subterranean Homesick Blues” and “Maggie’s Farm.”

At least as importantly, BIABH was the assertion of Dylan’s new musical identity. This statement was more profound since it was generally delivered implicitly, albeit repeatedly, throughout the album. Dylan’s desire for creative freedom, and for liberation from the folk music straightjacket, led to an album that explored what it meant to be creative. On BIABH, Dylan showed by example what artistic freedom in rock music looked and sounded like, while raising the bar on song lyrics and expanding the template for song themes. BIABH was both a statement and a demonstration of musical independence, and it changed the idea of what a rock musician could be.

The effects were dramatic, not least on Dylan himself. His next two albums, Highway 61 Revisited and Blonde on Blonde, continued Dylan’s sonic and lyrical adventures. Both are also widely regarded as among the best rock albums ever. The fact that all three of these albums were released over a fourteen-month period is inconceivable today, and it remains unparalleled in rock history.

Other musicians were also deeply affected by BIABH and Dylan’s subsequent work. Among those imbibing Dylan’s influence were the Beatles, then the world’s most popular rock band, who had taken America by storm in 1964. The Beatles met Dylan in the summer of 1964, and he shared with them some of the songs that would later appear on BIABH.

The meeting reportedly changed their view of the type of music they should be making. Shortly after BIABH was released, the Beatles began work on the songs that would be released as the Rubber Soul album in December 1965. Rubber Soul is a significant departure in the Beatles’ work, which transitions from the energetic, bright pop they had been making into more lyrically sophisticated and musically nuanced work. Although Rubber Soul doesn’t sound like BIABH, Dylan’s influence is evident and was clearly critical to the Beatles’ change in direction.

Rubber Soul also affected other prominent musicians, most famously Brian Wilson of the Beach Boys. Wilson was inspired by Rubber Soul to make Pet Sounds, which was released in May 1966. Pet Sounds was another groundbreaking record, particularly in its use of elaborate instrumentation and studio recording techniques.

After this, the floodgates were opened. Rock music was no longer founded on reworking delta blues and jump blues riffs, with a little surf and R&B mixed in for spice. An outpouring of music was released in a wide variety of forms that were scarcely imaginable before. Rock came into its own as a unique musical force, and it even developed a “classic rock” canon over the next decade or so.

In retrospect, it’s clear that rock and roll’s first decade, 1954-64, was very different from the decade that followed. There was an inflection point that changed the trajectory of rock, and it occurred around 1965. Of course, it’s silly to say that “one album changed everything,” or that only one album or artist contributed to this shift. Cultural change is both incremental and cumulative, reflecting a host of influences. But no album was more responsible for breaking the mold, or pointing the way forward to a more expansive and expressive type of rock music, than Dylan’s Bringing It All Back Home.