October is, of course, a good month to read horror fiction, given the obvious connection to Halloween and all the obsession with death and violence associated with that holiday, which has become a season in our culture such that it rivals Christmas in its cultural impact. As I noted earlier this month, this month is a good time to familiarize or re-familiarize oneself with the superb, innovative gothic writings of Edgar Allan Poe, who truly can be said to have invented the modern gothic horror genre.

October is, of course, a good month to read horror fiction, given the obvious connection to Halloween and all the obsession with death and violence associated with that holiday, which has become a season in our culture such that it rivals Christmas in its cultural impact. As I noted earlier this month, this month is a good time to familiarize or re-familiarize oneself with the superb, innovative gothic writings of Edgar Allan Poe, who truly can be said to have invented the modern gothic horror genre.

Poe was also a master of, and really the inventor of, the mystery fiction genre. Mystery fiction, of course, has some commonalities with gothic horror fiction, in particular the thematic emphasis on death and violence, though mystery fiction typically resolves the story with a demonstration that any seemingly supernatural elements were matters of false interpretation and explainable by natural processes. Hence this is a good month to enjoy mystery fiction and learn more about it.

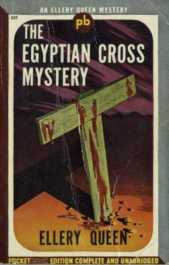

One of the greatest of all mystery writers was Ellery Queen (actually two men, Frederick Dannay and Manfred Lee, sometimes with additional ghostwriters as well, toward the end of their career, which lasted from the late 1920s to the early 1970s), and his combination of surrealism, gothic imagery, unpretentious but insightful probing into psychology and philosophical issues) and fair-play mystery puzzle-construction was an essential step in the construction of modern American mystery fiction.

(For a modern creation that clearly reflects the spirit of Ellery Queen, see the ABC-TV series Castle.)

Some of the Ellery Queen novels are perfect for this time of year, and at the excellent Classic Mysteries website, mystery fiction expert Les Blatt writes insightfully and informatively about one of the very best Queen mysteries: The Egyptian Cross Mystery. The book was written rather early in the pair’s career (1932), and it includes plenty of gothic elements and unsettling imagery, yet it resolves the story in a quite satisfactory and somewhat inspiring way.

The Egyptian Cross Mystery is in fact not only a great mystery but an exemplary one. It pioneered a style which countless writers would follow in the decades to come.

Blatt introduces the subject of the novel enticingly:

When we talk about America’s contributions to the Golden Age of Detective Fiction, those years between the two world wars, I know too many readers who begin to stifle yawns. Traditional, puzzle-oriented American mysteries, they say, were so dull, so cerebral, and so on and so forth. No blood. No guts. Ho hum.

Have I got a book for you.

Beheadings. Crucifixions. Cults. Nudists. An apparent multiple murderer. No apparent rhyme or reason – or so you are led to believe.

Later in his article (which links to a podcast about the book), Blatt describes the plot as follows:

In The Egyptian Cross Mystery, Ellery Queen is intrigued when he hears about the gruesome murder in West Virginia of a local schoolmaster, whose body is found hanging from a T-shaped signpost, his head missing. Ellery thinks that there might be a connection to Egyptian mythology and religion – a belief nurtured by the presence near the murder scene of a sun-worshipping cult.

Months later, there is a similar murder, this time at an estate on New York’s Long Island. The victim has been murdered in the same horrifying manner as the man in West Virginia. Ellery Queen gets involved in the investigation, and the case quickly becomes even more complex and bizarre – and, once again, that cult of sun-worshippers is on hand. There are plenty of red herrings, and more murders – and plenty of clues for the reader to follow. And, of course, it all ends with a challenge to the reader: the authors tell us that we have all the clues Ellery Queen needed to solve the case – can the reader do it first?

I couldn’t. Could you?

Blatt concludes with this evaluation: “It’s a terrific—if gory—read.”

I fully agree. You can read the full review and access the podcast here: http://www.classicmysteries.net/2014/10/the-egyptian-cross-mystery.html.

The Egyptian Cross Mystery is available in an excellent Kindle edition. Here’s a passage from the book that conveys its effectiveness, in which Queen describes the crime scene through a fictional news story:

The Egyptian Cross Mystery is available in an excellent Kindle edition. Here’s a passage from the book that conveys its effectiveness, in which Queen describes the crime scene through a fictional news story:

The most pitiful Christmas story of the year was revealed today when the beheaded body of Andrew Van, 46-year-old schoolmaster of the little West Virginia hamlet of Arroyo, was discovered crucified to the signpost on a lonely crossroads near the village early Christmas morning.

Four-inch iron spikes had been driven into the upturned palms of the victim, impaling them to the tips of the signpost’s weatherbeaten arms. Two other spikes transfixed the dead man’s ankles, which were set close together at the foot of the upright. Under the armpits two more spikes had been driven, supporting the weight of the dead man in such a way that, his head having been hacked off, the corpse resembled nothing so much as a great letter T.

The signpost formed a T. The crossroads formed a T. On the door of Van’s house, not far from the crossroads, the murderer had scrawled a T in his victim’s blood. And on the signpost the maniac’s conception of a human T.…

Why Christmas? Why had the murderer dragged his victim three hundred feet from the house to the signpost and crucified the dead body there? What is the significance of the T’s?

Local police are baffled. Van was an eccentric but quiet and inoffensive figure. He had no enemies—and no friends. His only intimate was a simple soul named Kling, who acted as his servant. Kling is missing, and it is said that District Attorney Crumit of Hancock County believes from suppressed evidence that Kling, too, may have been a victim of the most bloodthirsty madman in the annals of modern American crime.…

Shortly thereafter, Queen describes the coroner’s inquest, and the following weird scene ensues:

There was a stir, and in the rear of the courtroom a queer figure rose. It was that of an erect old man with a bushy gray beard and overhanging eyebrows. He was dressed in tatterdemalion garments—a conglomeration of ancient clothing, torn, dirty, and patched. He shambled down the aisle, hesitated, then wagged his head and sat down in the witness chair.The Coroner seemed nettled. “What’s your full name?”“Hey?” The old man stared sidewise out of bright unseeing eyes.

“Your name! What is it—Peter what?”

Old Pete shook his head. “Got no name,” he declared. “Old Pete, that’s me. I’m dead, I am. Been dead twenty years.”

There was a horrified silence, and Stapleton looked about in bewilderment. A small alert-looking man of middle age, sitting near the Coroner’s dais, got to his feet “It’s all right, Mr. Coroner.”

“Well, Mr. Hollis?”

“It’s all right,” repeated the speaker in a loud voice. “He’s daffy, Old Pete is. Been that way for years—ever since he popped up in the hills. He’s got a shack somewhere above Arroyo, and comes in every couple of months or so. Does a little trappin’, I guess. Got pretty much the run of Arroyo. A regular character, Mr. Coroner.”

“I see. Thanks, Mr. Hollis.”

The Coroner swabbed his fat face, and the Mayor of Arroyo sat down in a murmur of approval. Old Pete beamed, and waved a dirty hand at Matt Hollis. … The Coroner continued brusquely. The man’s replies were vague, but enough was elicited to make formal confirmation of Michael Orkins’s story, and the hillman was excused. He shuffled back to his seat, blinking.

As that scene indicates, Queen was a master at incorporating elements of courtroom drama in mysteries, and the pair also pioneered the police procedural approach to crime fiction, in their first book, The Roman Hat Mystery.

As noted earlier, The Egyptian Cross Mystery is available in Kindle book form, and is well worth reading.