During recent years, Heston was known less for his acting than for his presidency of the National Rifle Association—an honorable endeavor which many in Hollywood and the rest of the mainstream media characterized as an oddball, fringe organization. This from an industry that makes much of its fortune off of violent films, TV programming, and video games that rely on depictions of gunplay.

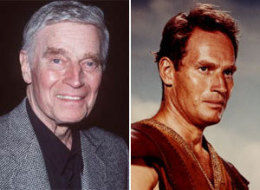

Long before he became an advocate for gun owners’ Second Amendment rights, Heston was a justly acclaimed actor. He rose quickly through the ranks during the 1950s, when most other prominent male movie actors were exploring their sensitive sides and representing adolescent rebellion—such as James Dean, Montgomery Clift, and Marlon Brando. Heston provided a strong contrast, which his iron jaw, chiseled features, and imposing physical size and strength.

Physically rather like his contemporary Rock Hudson but a far superior actor, Heston specialized in larger-than-life roles such as Moses (playing the character brilliantly at a very young age in Cecil B. DeMille’s classic The Ten Commandments), Judah Ben-Hur (in the superb William Wyler film Ben-Hur), Buffalo Bill Cody (Pony Express), and Gen. Andrew Jackson (later president, of course) in The Buccaneer.

Likewise impressive and notable are his 1960s performances in El Cid, 55 Days at Peking, The Greatest Story Ever Told, The Agony and the Ecstasy, The War Lord, and Khartoum.

Heston also took characters who were not in themselves larger than life and made them so, as in his performance as the circus troupe leader in The Greatest Show on Earth, Christopher Leinengen in The Naked Jungle, and Steve Leech in The Big Country. Just try to imagine Clift or Brando in those roles; their intense interest in self-expression would have ruined the films.

As American society and culture soured and became increasingly disturbed and cynical during the second half of the century, in the late 1960s and early 1970s he was a rare man of strength, dignity, and honor in films such as Planet of the Apes, Soylent Green, and The Omega Man.

But his time was really over by the mid-1970s, as Hollywood increasingly purveyed the demoralized New Left notion that there were no longer any real heroes in the world, only antiheroes, and replaced the Hestons of the world with cynical, self-centered antiheroes played by Clint Eastwood, Al Pacino, Robert DeNiro, and the like.

But his time was really over by the mid-1970s, as Hollywood increasingly purveyed the demoralized New Left notion that there were no longer any real heroes in the world, only antiheroes, and replaced the Hestons of the world with cynical, self-centered antiheroes played by Clint Eastwood, Al Pacino, Robert DeNiro, and the like.

Yet Heston could still turn in an impressive performance when allowed, as in Richard Lester’s The Three Musketeers and The Four Musketeers, in which he played Cardinal Richelieu with both subtlety and great command.

A truly brilliant moment occurs at the end of The Four Musketeers when Richelieu gives in and allows D’Artagnan (Michael York) his freedom and a position in the King’s Musketeers. D’Artagnan goggles in amazement, and Richelieu, casually leaning back in his chair with his hands resting on the arms, flicks a hand dismissively without even raising it from the arm of the chair, sending the young musketeer out of his presence.

Very, very few actors have had the presence to bring off a moment such as that, and in my view it is a great moment in the art of film performance.

Heston was politically of the right, a good friend of Ronald Reagan and philosophically in strong agreement with him. Heston’s political position was that of a classical liberal, and his strong advocacy of gun owners’ rights was part and parcel of it and showed his great courage and fortitute in taking a position so unpopular in his industry.

He was a great actor and a great man.

A wonderful tribute to the greatest actor of all-time. Heston influenced Arnie, Sly and Indy Jones.