What Kind of U.S. Culture?

By S. T. Karnick

It is a truism that the right has been losing the culture for the past few decades. Since the end of World War II, the American culture has trended toward ever-greater promotion of narcissism, self-expression, antinomianism, identity politics, and questioning of all conventions and authority. It has become an instrument for the devaluation of all values.

What kind of culture we should want is actually an important question that has yet to be answered satisfactorily. Most conservatives simply want a conservative culture. That may sound very fine, but it is an impossibility, if only for practical reasons regarding the current situation, with liberals being embedded firmly in all of our cultural institutions.

Even more importantly, before we can change the political, moral, or social point of view of a culture we must understand the mechanisms by which a culture works. More than anything, a culture is a place. Like the economy, it’s the market in which ideas and expressions of the human imagination are developed, fostered, and traded. A perceptive look at a particular culture will indeed reveal the moral and intellectual values of a society, and a culture fosters reform or decay of those values. It does so in the same way the economic marketplace indicates and creates a forum for people’s creativity and diligence.

What we should want, then, is a free culture.

To see why this is so, we should start with a description of what a free culture looks like. The answer is that it’s messy, vibrant, organic, ugly, beautiful, rich, and productive. A free culture looks like a free economy—it’s by no means perfect, and it will not provide only what some particular group wants, but it will provide pretty much everybody with what they want if we allow it the freedom that such a flourishing requires. It’s up to the culture, and the people of the society who constitute it, to provide a varied supply of products, and it’s then up to social and spiritual leaders to encourage people to want the right things.

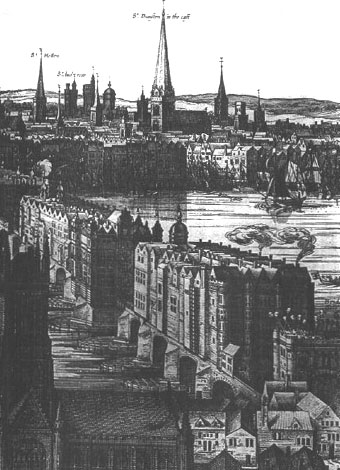

Two excellent examples of such cultures are Elizabethan and Augustan Britain, where a strong, relatively free culture widely reflected what is best in the human spirit through drama, music, prose, poetry, painting, and the like. Not everything in these cultures was salutary and beautiful, to be sure, but certainly they are impressive in their accomplishments, especially when compared to our current cultural miasma. These cultures, it should be noted, were relatively free, not perfectly free. Censorship of the theater was in place, for example, and public obscenity was illegal. Yet the freedom to trade ideas was paramount—in great contrast to our society today, where public obscenity is rampant but intellectual freedom is under continual assault.

Two excellent examples of such cultures are Elizabethan and Augustan Britain, where a strong, relatively free culture widely reflected what is best in the human spirit through drama, music, prose, poetry, painting, and the like. Not everything in these cultures was salutary and beautiful, to be sure, but certainly they are impressive in their accomplishments, especially when compared to our current cultural miasma. These cultures, it should be noted, were relatively free, not perfectly free. Censorship of the theater was in place, for example, and public obscenity was illegal. Yet the freedom to trade ideas was paramount—in great contrast to our society today, where public obscenity is rampant but intellectual freedom is under continual assault.

Here the analogy to the economic market is useful. In the economic market, laws against usury, slavery, fraud, and other exploitative activities ensure that the freedom to pursue salutary activities is unimpeded by either government or private actions. In the culture, strictures against public obscenity, indecency, and the like serve the same function, for a culture that presents too many such temptations makes people slaves to their baser appetites. The question then becomes not whether these things can or should be regulated by society, but what is the proper amount of regulation. And the answer is, whatever gets us closest to being a truly free society.

Of course it’s true that as many people in a free market will eat potato chips and buy blue jeans that are two sizes too tight, and in a free culture many will watch MTV, read romance novels, and listen to infantile music. But a free economic market gives people the variety and opportunity to make good choices, and so it is with a free culture. A truly free culture will have much that we don’t like, but it will have plenty of room for what we do like.

The most urgent question, then, in my view, is not whether we will have a good culture or a bad one, but is instead whether we shall have a free one or one controlled by a self-appointed class of our “betters.” Even if the desire for a conservative culture is laudable, the forcible creation of a particular vision for the culture is the perpetual dream of statists who would control the population to fit their utopian schemes. We should not look upon the culture as perfectible. Just as statists and utopians hate and fear economic freedom, so also do they despise and dread cultural freedom. That is a leftist vision, not a conservative, liberal, or libertarian one.

A fundamental principle of the right is that people and society are not perfectible. Hence, we must bear in mind that the culture will always be ripe for improvement and will never be perfect, while we continually strive for its betterment.

A fundamental principle of the right is that people and society are not perfectible. Hence, we must bear in mind that the culture will always be ripe for improvement and will never be perfect, while we continually strive for its betterment.

While one danger is in viewing the culture from a statist perspective, many on the right (deep in the libertarian corner), actually revel in what is awful in the culture. They correctly celebrate variety, but they neglect to understand the need for a certain amount of order. Just as in the economy it is important for there to be protection from exploitation and damage to others’ property, so too in the culture must some rules be in place, to prevent the innocent, particularly children, from being wantonly corrupted and exploited. And in our society, our Founders rightly placed that responsibility in the separate states and the local community, reflecting the thinking of the great Whig liberal Edmund Burke.

As the mention of Burke suggests, this is a vision that should make great sense to Christians, and although American Christianity has always had a strong strain of Puritanism, the similarity between cultural freedom and religious liberty should make the idea of a free culture strongly appealing to the Christian Right.

The idea of a free culture should appeal strongly to the fundamental values of the vast majority of Americans. The important question then becomes what kind of ideas we should seek to promote in such a culture. We certainly know what is wrong with our contemporary culture: the ever-greater promotion of narcissism, antinomianism, questioning of all conventions and authority, identity politics, and the devaluation of all values, as noted earlier. And all these things that seem so liberating actually tend to enslave people to their baser appetites. Far from either fostering real freedom or manifesting it, our current culture imposes a clear set of values on society, and they are not ideas that strengthen freedom but instead constrain it.

The answer to the current cultural regime is a culture of liberty. By fostering greater respect for personal liberty and encouraging a national conversation about it, a culture of liberty could work toward a long-lasting reversal of the deleterious social and political trends that have resulted from the intellectual and cultural ills of the past half-century. For example, a culture of liberty could promote community by allowing natu

ral bonds to form among individuals as they recognize that the state is not the solution for their problems. It could strengthen marriage, family values, and personal responsibility by showing the terrible effects of government intervention in these areas and allowing people to see the disastrous consequences of dissolute personal behavior. It could increase the public’s understanding of and respect for the social values that long underpinned American society, by allowing religious groups fair and open access to the public square.

In fact, many of these things are happening already and would benefit greatly from a concerted effort to foster a culture of liberty.

The press for a truly free culture would emancipate the right from popular accusations that we wish to control people through fear and force, which I have called the Theocracy Smear. Quite to the contrary, this vision does not need to be imposed by force, because it comports with reality and with human nature. It is Thomas Jefferson’s political idea applied to culture: the understanding that the truth has the best chance to thrive when ideas are allowed to be expressed freely. As the religious historian Philip Jenkins has noted, the United States is the most religious major nation in the entire world precisely because of our religious freedom—the imposition of a state church actually reduces attendance and belief. Just so with the culture: respect for both freedom and traditions will thrive in a truly free culture because they are both very good things.

The good news is that we are heading toward just such a culture, and there are ways we can encourage that transition and foster a culture of freedom. The development of what I call the Omniculture provides an opportunity to affect the culture as social and technological change break the bonds of the left-liberal establishment. An understanding of the Omniculture and how it works should prove valuable to those who want to to foster a good, true, and attractive alternative to the anti-authority, antinomian, hyperindividualistic cultural products that currently flood our society. The pursuit of a culture of liberty is the critical first step in reclaiming the American culture.