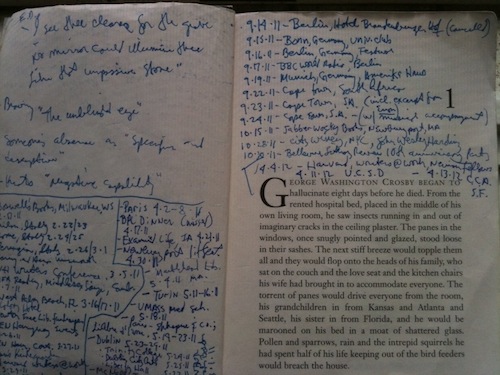

Do you write comments in the margins or the covers of your books? If you do, according to an anonymous editor from a century ago, it’s a clear sign that the author has in some way touched you on a deep level, moving you to a response which can take almost any form, from derision to scorn to disbelief to astonishment to laughter — the list is endless.

From the beginning of book publishing, many readers have had no compunctions about marking in books. Our editor tells us that such marginalia can over a span of years unite today’s reader with not just one mind — the author’s — but also another mind, that of the scribbler who was moved to his or her comment. To him, this is a very good thing indeed:

From the beginning of book publishing, many readers have had no compunctions about marking in books. Our editor tells us that such marginalia can over a span of years unite today’s reader with not just one mind — the author’s — but also another mind, that of the scribbler who was moved to his or her comment. To him, this is a very good thing indeed:

OF our books, none have a life so much their own as those wherein there still crops out the genius not of an author alone, but of a reader worthy of that author. A keen intelligence has passed that way; in passing, it has conveyed to an inanimate object the stir of its own life. The thought of the writer has been taken a stage farther on in the journey toward truth; else it has been led into one of the untrodden by-paths. Or perhaps the text the text has been tortured with interlineations by one who proves himself no mean antagonist; the margins have been stabbed, not with imbecile interrogation points, but with ironical rejoinders, with taunts, in the face of which the author is cruelly condemned to silence. Questioned and questioner are alike departed; perhaps they walk arm-in-arm by the Styx bank, amicable in their discussion of the points at issue.

At its best, on such occasions two minds can combine to produce something greater:

A book well read and somewhat scarred by the reader’s pencil is become a part of him — a member of his spiritual body.

This editor’s metaphysics might be a little shaky, but the point is well made that agreeing or arguing with an author in writing rather than just scanning what they’ve written can lead a reader to a more profound understanding:

Not great men alone have scribbled on the edges of books they loved or quarrelled with. Nor was the practice limited strictly to schoolgirls’ scribblings in the current novels. Those were days when every man of scholarship or substance took pride in his books; the era of the levelling public library was not yet come. And with the more personal feeling that the reader had in those bygone days (remember, he had fewer books, but he read them through!) that reader was apt to have a genuine tête-à-tête with the writer himself, before the volume was laid down.

But not just understanding. Our editor spends fully half of his piece in a charming account of a second-hand book from his collection in which a man, clearly in love with an anonymous woman, used marginalia to convey his feelings to her:

Finally he took a step that I commend to you, all lovers that have been rejected once in love, and yet would try again. He gave the book (and a flower pressed in it that he had plucked off Shelley’s grave) to the maiden that had said him no . . . And he begged her — on a fly leaf — to regard his heart outpourings on the various pages (all very neatly written with the sharpest of hard pencils) as thoughts that he had set down only for himself, as he had then supposed; that belonged to her too, however, since she was their single inspiration.

You can read the entire article from Scribner’s (“On Marking in Books,” June 1910, 3 pages) here.