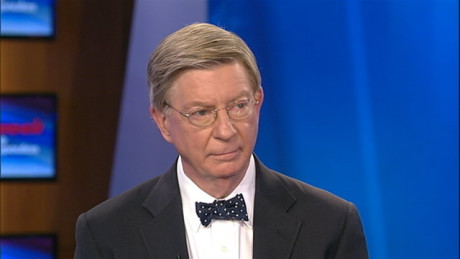

Most people would probably agree that giving someone something for nothing does not promote self-reliance. Unfortunately, much of our government policy intended to ameliorate poverty does just that, and it has real consequences in the lives of real people. Columnist George Will noted that recently, citing a study by demographer Nicholas Eberstadt in National Affairs quarterly that documented how entitlements inculcate dependency. Will notes that more than a third of Americans are considered “needy” by the federal government and thus receive some form of need-based payments.

Most people would probably agree that giving someone something for nothing does not promote self-reliance. Unfortunately, much of our government policy intended to ameliorate poverty does just that, and it has real consequences in the lives of real people. Columnist George Will noted that recently, citing a study by demographer Nicholas Eberstadt in National Affairs quarterly that documented how entitlements inculcate dependency. Will notes that more than a third of Americans are considered “needy” by the federal government and thus receive some form of need-based payments.

Eberstadt’s statistics show that the growth of such payments over the last five decades has been startling, Will notes:

Transfers of benefits to individuals through social welfare programs have increased from less than 1 federal dollar in 4 (24 percent) in 1963 to almost 3 out of 5 (59 percent) in 2013. In that half-century, entitlement payments were, Eberstadt says, America’s “fastest growing source of personal income,” growing twice as fast as all other real per capita personal income. It is probable that this year a majority of Americans will seek and receive payments.

It might seem that Medicare and Social Security are the cause of this growth, but Will points out that is incorrect; means-tested entitlements are the source of the increase:

Between 1983 and 2012, the population increased by almost 83 million—and people accepting means-tested benefits increased by 67 million. So, for every 100-person increase in the population there was an 80-person increase in the recipients of means-tested payments. Food stamp recipients increased from 19 million to 51 million — more than the combined populations of 24 states.

Remarkably, the percentage of the U.S. population below the poverty line has remained relatively stable over the last 30 years despite the government having spent literally trillions of dollars of taxpayer money on ameliorating poverty. What has changed in recent years is that Americans don’t have to be defined as poor to receive government aid, but need only be defined simply as needy; more than half of those receiving such benefits today are needy but not poor.

The consequence of such extravagant benevolence, Eberstadt argues, is a change of America’s national character, and not for the better. Will concludes his column with the following sobering words:

Daniel Patrick Moynihan, a lifelong New Deal liberal and accomplished social scientist, warned that “the issue of welfare is not what it costs those who provide it but what it costs those who receive it.” As a growing portion of the population succumbs to the entitlement state’s ever-expanding menu of temptations, the costs, Eberstadt concludes, include a transformation of the nation’s “political culture, sensibilities, and tradition,” the weakening of America’s distinctive “conceptions of self-reliance, personal responsibility, and self-advancement,” and perhaps a “rending of the national fabric.” As a result, “America today does not look exceptional at all.”

Will’s column is another reminder—as if one were still needed—that government policies create an ever-increasing spiral of dependency by undermining the culture and the character of the people.

The Republican Party has failed to stop Obama because it is unable to articulate what he has done wrong besides violating the processes and procedures of government. Its establishment is unable to convincingly debate him because they agree with his premises while challenging his processes.

Bradley, I agree that the Republican Party has shown far too little courage.