Thirty years ago, this writer was granted an assignment to review a B. B. King concert at Michigan State University. As a music junkie who moonlighted as an English major soon to graduate, it couldn’t have come at a more opportune time–I needed some clips for my portfolio just in case I got a call to write for Rolling Stone or Musician magazines.

The bar scene in East Lansing was no stranger to the blues, featured as it was on the Midwest tour of such blues labels as Alligator and Rounder. On any given week, a nearly destitute student could scrape together a few bucks to sit at a local watering hole while enjoying live performances by Lonnie Brooks, Albert Collins, Buddy Guy, Junior Wells, A.C. Reed, and a host of others. After living for a year in North Chicago, where I received an extensive education in blues on vinyl and performed live, however, East Lansing was methadone. But a free ticket to see B.B. King–and Bobby “Blue” Bland–on a big stage? Be still my blues-beating heart!

The concert bordered on the sublime. King shared the stage with Bland, and the pair performed their respective hearts out. I saw King perform several more times over the ensuing decades, but never more charged than he was that night, which, it must be admitted, was already in an era well past his prime. He had yet to record with U2–a band of which I was never particularly fond, but their King collaboration, “When Love Comes to Town,” always makes me smile in appreciation–appear on numerous television commercials and movie soundtracks, or turn into what our culture categorizes as an “icon” (an overused term that, as a result, now means next to nothing).

King indeed was a terrific ambassador for blues music, which unfortunately took a turn for the worse when overrun by singers emulating but failing miserably to approximate his growling vocal style. Whereas King transmitted emotion, too often his imitators simply seemed in dire need of a laxative. I’ll spare the reader a list of the top offenders, but I will gladly name some of the guitarists who successfully borrowed from King’s Big Book of Riffs. Peter Green, founder of the original Fleetwood Mac, is at the top of the list, and is reportedly the British blues boom guitarist most admired by King himself. Eric Clapton also belongs on the list, and his collaborative CD with King is too often neglected in overviews of both artists’ work. One could also make the argument for John Fogerty and Jeff Beck as King disciples.

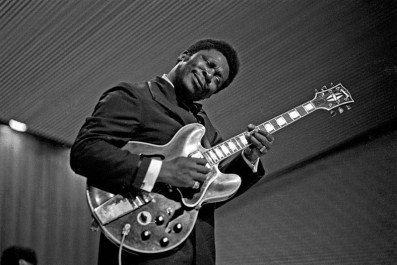

What I witnessed that night in 1985 wasn’t exactly the caliber of Live at the Regal–recorded more than two decades prior–but there was still plenty to admire, as could be said about each time I saw him perform afterward. Sure, his stage powers diminished with age, but B. B. King continued to deliver the goods based on a style he developed early on, including altering the tunings on his guitar to either mimic a Hawaiian guitar or blues harmonica. True, he never learned to sing and play at the same time, but he added stinging guitar lines to punctuate the lyrics he sang, and did so magnificently.

Of course, one divorces the personal life of an artist from the performance side. There’s not much to admire in a man who may have fathered 15 children from 15 different mothers, for example. In this regard, it must be noted, B. B. is not so much a king as a cad.

artist from the performance side. There’s not much to admire in a man who may have fathered 15 children from 15 different mothers, for example. In this regard, it must be noted, B. B. is not so much a king as a cad.

It’s his music for which B. B. King will be remembered, however. He may not have been the greatest songwriter, guitarist, singer, and showman in the genre–and I would argue he’s definitely not tops in any of the previously named categories–but he was certainly the face, voice, and guitar most associated with the blues. For that, we celebrate more than 15,000 live performances, numerous albums, and 70 years of performing. Take a bow, Mr. King. Rest in peace, sir.