I have previously written of the unique film-making style of Robert Bresson (who died in 1999), whom I consider to be the supreme master of film. Recently, I viewed again his Lancelot du lac (1974) and it brought home to me once more the purity and intensity of his poetic minimalism and the sense of mystery that it evokes. It is a minimalism that eschews theatricality (he used non-actors whom he thought of, and referred to, as models) and pictorialism in order to to plumb more deeply the human condition.

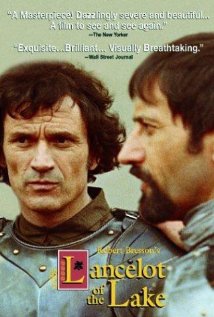

The Arthurian cycle of stories is one of the great European legends, of course. Bresson’s film is a tragedy about Arthur’s kingdom’s final crisis. The film, which won the International Federation of Film Critics Prize at Cannes, opens with violence–scenes of death, destruction, and sacrilege– as the knights, led by Lancelot (Luc Simon), fail in their quest for the holy grail (a chalice in which Joseph of Arimathea captured some of the blood of Jesus). It is, in part, a tale of betrayal: the adultery of Lancelot and Arthur’s Queen Guenievre (Laura Duke Condominas) and the rebellion of Mordred (Patrick Bernard) against Arthur (Vladimir Antolek-Orosek). While Lancelot is the title character, Guenievre looms at least as large. She is strong-willed and passionate, not hesitant to make self-confident, if sometimes debatable, pronouncements. Just as Lancelot and the other knights live in tents amongst their neighing, sweating horses, Guenievre lives in the castle with her female attendants. Arthur, quite a decent man but not a strong leader, is deeply troubled by the quest’s bloody failure. Indeed, most everything seems to fail: romantic love, friendship, loyalty, repentance. Even the courage of the noble knight Gauvain (Humbert Balsan) cannot save the situation. Merlin being dead before the film begins, the only one who seems to have a grasp of things is an old seeress, but she has little influence.

The tale the film tells is a dramatic one, but it is what I have called the poetic minimalistic manner of its telling that makes the film so powerful. This is most obvious in a jousting scene and in the depiction of the war between Arthur and Mordred, but it is also displayed in more subtle ways such as an, at first, cryptic crackling noise during a conversation between Lancelot and the seeress of Escalet.

I know of no more profound version of the Arthurian legends than this film. Though the magic of Merlin is missing from it, Bresson weaves a mesmerizing magic of his own.